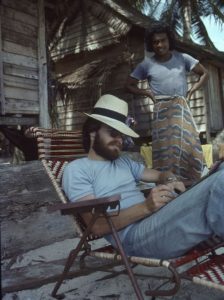

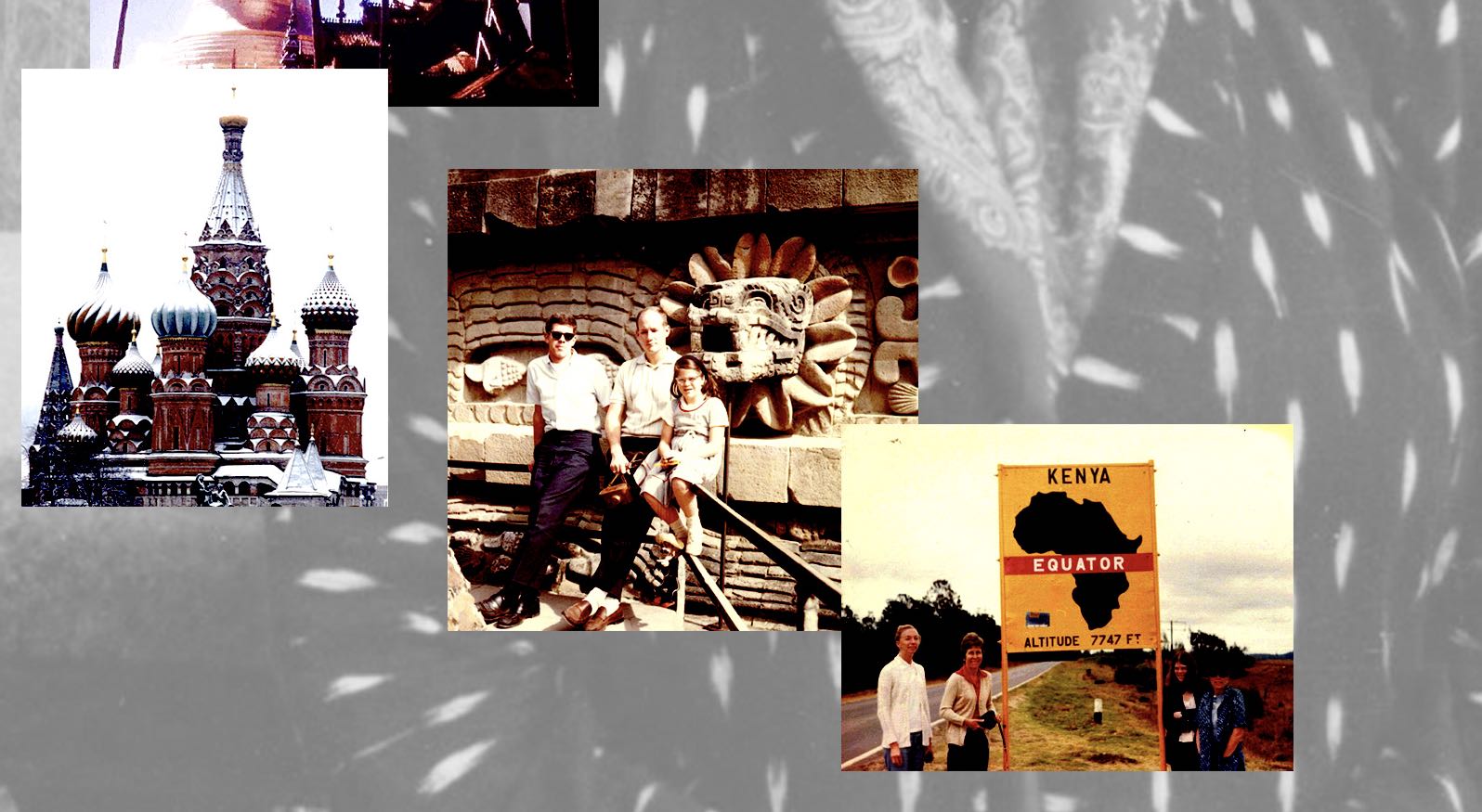

In 1976, young Australian journalist and Third Culture Adult Keith Dalton packed a typewriter and a cassette recorder into his backpack and set off on an 18-month, six-country journey through Southeast Asia.

Dalton’s goal from the age of 10 was simple — to become a foreign correspondent.

“From that young age, the idea of becoming a foreign correspondent consumed me until, at the age of 25, I left Australia,” he writes. “I needed to make that dream a reality.”

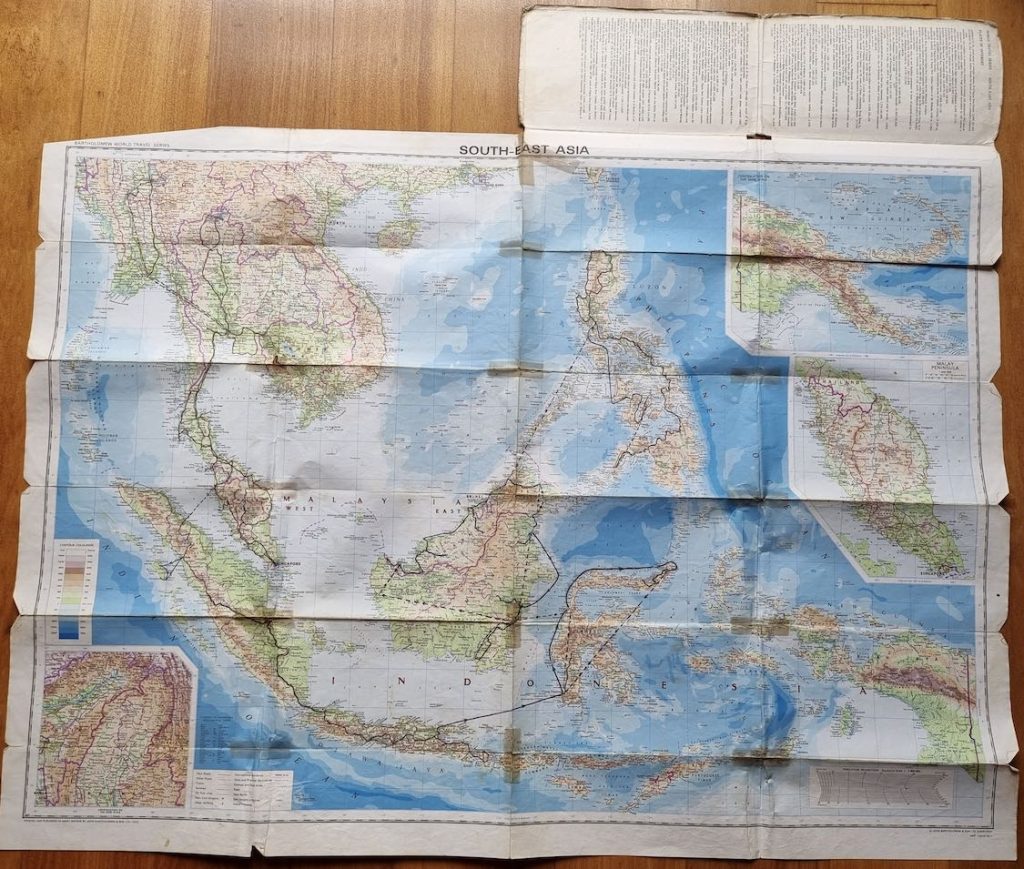

These were the days before mobile phones, laptops and the Internet. So along with his typewriter and cassette recorder, Dalton crammed a large map, spare typewriter ribbons and batteries (for an AM and shortwave radio), and two dictionaries into his backpack.

After years of training at “The Sun Herald” and Radio Australia in Melbourne, in “blokey,” male-dominated newsrooms where women poured the tea and men pounded out their typewritten stories in a cigarette haze, Dalton left Australia, without an itinerary or a return ticket, to find the stories that really mattered.

He didn’t return home for 12 years.

TAKING THE LONG WAY AROUND

Unlike others chasing fast routes and big breaks, Dalton took the long way around.

“I could have boarded a plane in Melbourne and disembarked in Manila in 12 hours, but if I had done that – flown from ‘A’ to ‘B’ – everything beneath would have gone unseen,” he writes. “Why travel from ‘A’ to ‘B’ in the air when you have the entire alphabet to choose from on the ground? And why hurry?”

That philosophy, a refusal to rush and a hunger to truly see, is the heart of “Meandering to Manila,” a memoir about exploration, endurance and the making of a journalist.

Nowadays, it’s an adventure that would almost be impossible to repeat.

Dalton’s unplanned route from Melbourne to Manila took him through Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Burma and Borneo on truck-like buses, dilapidated trains, rust-bucket cargo ships and motor-powered canoes.

RAW AND UNPOLISHED

He traversed a Southeast Asia that was raw and unpolished, still untouched by the convenience of mass tourism. Roads vanished into jungle tracks, bridges were planks laid across streams and maps often lied. At every border he crossed, there was a new currency, new procedures and a new test of patience.

Yet, every mishap — every delay, every wrong turn — deepened his understanding of a region straddling tradition and transformation.

Dalton slept in rat-infested $1 hotels. As a stowaway on an Indonesian inter-island “rust bucket” cargo ship, he ate nothing but rice and half a boiled egg, sometimes a dried sardine, every breakfast, lunch, and dinner for four days.

Upriver in central Borneo, it was more than a month before he saw another foreigner.

“For villagers and for river traders, canoes are the only way to reach isolated hamlets and homes — tiny human outposts — almost swallowed up by a canopy of never-ending jungle,” he writes. “These river taxis supply a vast network of remote villages and scattered indigenous tribes. They carry as many passengers as the water level allows; load as much cargo as possible; follow no timetable; make as many stops as needed; and go upstream as far as required. Nothing is routine. Everything changes.”

A TRUE FOREIGNER

The most unforgettable moment was when Dalton discovered he was the first white person ever seen by the children of ex-headhunters. They stroked the unfamiliar hair on his arms, poked at his clothes, marveled at his boots and took turns to view a blurred world through his glasses.

Later, Dalton watched the children — and some adults — try to “shake the voices” out of his radio. He stayed in a tribal “longhouse” where six shrunken heads hug from a crudely fashioned veranda.

“I look up and stop in my tracks. There, before me, dangling from the veranda posts of the longhouse, are six severed heads,” he writes. “They are nothing like I had imagined. From this distance, they appear three-quarters the size of a normal head — black, rubbery and gruesomely disfigured.

“The heads are hung by their hair from veranda posts or contained inside a hanging bamboo basket,” he continues. “They’re respected and revered. They are guardians. They bring equanimity to the longhouse. It is believed the severed heads encase the souls of the deceased – their status, skills, physical power, and mental strength — and hanging these heads, at intervals, along the length of the longhouse veranda is believed to bring peace, health, and well-being to the families.”

Dalton witnessed his first killing on the Thai-Malay border, when a communist guerrilla, who sat next to him on a bus, was ordered off the vehicle by soldiers and moments later was shot dead in a scuffle.

There, before me, dangling from the veranda posts of the longhouse, are six severed heads.

One of only 11,000 people allowed to enter Burma in 1976, Dalton travelled on rattly pre-Second World War trains. The toilet was a hole in the carriage floor with a round metal hatch cover above the tracks — which required a balanced squat and a good aim.

In Sumatra, a 250-kilometer/155-mile bus journey took two days, after the vehicle suffered two flat tires and was bogged nine times.

Along the way, Dalton contracted malaria, dysentery and kidney stones. Each illness struck in a different country, and with each one he survived through sheer determination and the kindness of strangers.

‘Malaria,’ was all he said, before disappearing… I saw him twice more that night… After five days and three soaked mattresses, I finally mustered the strength for a staged recovery – from lying in bed, to sitting on the side of the bed… to propping myself against a wall to pull up my pants. Finally, I was able to pack my bag, take the one flight of stairs down to the foyer, and emerge into the sunlight.

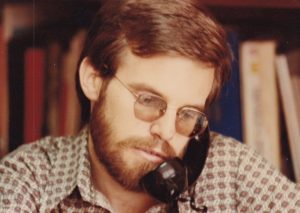

At night, Dalton washed his clothes in hotel basins, stretched string between light fittings to dry them, and typed freelance features for newspapers and magazines in Melbourne, London and Hong Kong. By day, as he traveled, he wrote long letters to his parents back in Australia — one stretched to 16 pages.

BRINGING THOSE LETTERS TO LIFE

Those “Dear Mum and Dad” letters are now the lifeblood of “Meandering to Manila.” For almost 50 years, those letters remained unread in a shoebox. They bring to life an era when communication took weeks and travel demanded patience, grit and curiosity.

Dalton was both recorder and commentator. His eye for observation was sharp, his honesty cutting. His writing in “Meandering to Manila” captures the humor and hardship of a disappearing world, a world without screens, schedules or certainty.

He describes the journey as his “journalistic baptism.”

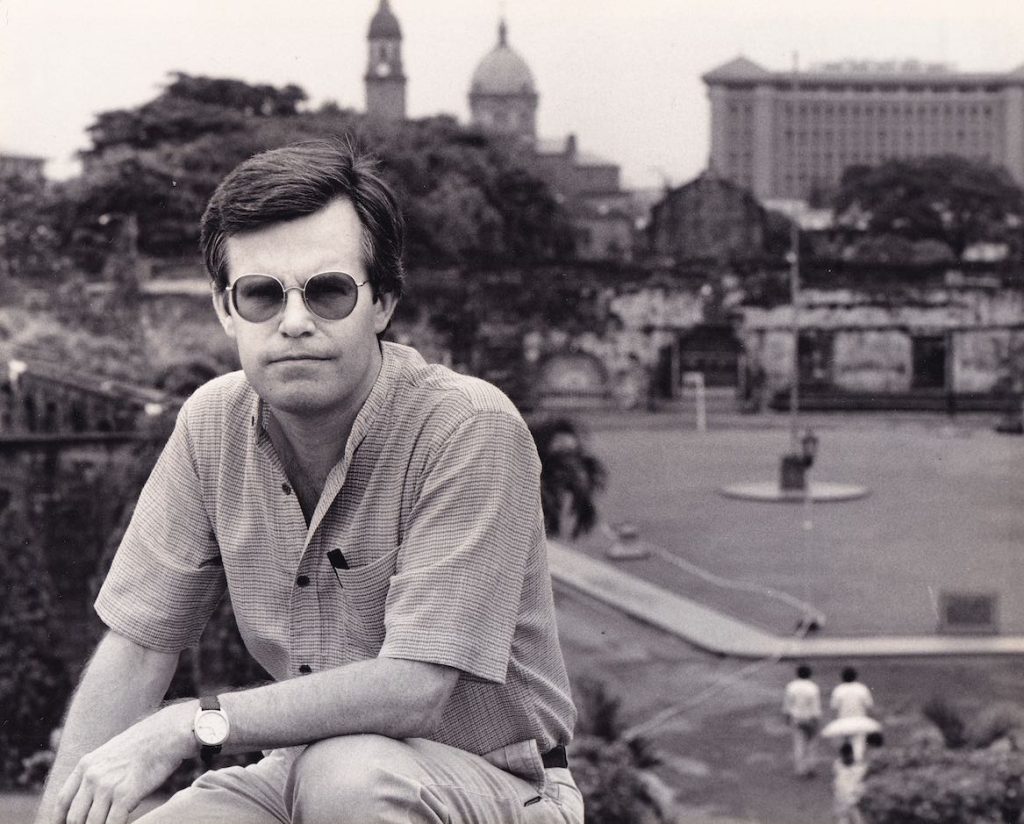

Eventually, arriving in Manila and not knowing a single soul, Dalton recorded his first report for Radio Australia inside a wardrobe. One station soon became 10 radio stations and three newspapers, including the BBC and The Times, ABC Radio, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian, American Broadcasting Company (ABC), National Public Radio (NPR) and Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS), and occasionally The Washington Post, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), Radio Netherlands, Radio New Zealand and Radio Television Hong Kong.

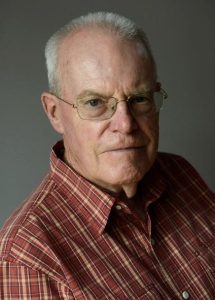

More than 40 years have passed since that young journalist traveled through Southeast Asia with a typewriter in his backpack becoming a “self-made” foreign correspondent.

“Meandering to Manila” is a time capsule of Southeast Asia in the 1970s, seen through the eyes of a young journalist who chased truth over comfort and curiosity over convention, determined to see the world as it was and not as depicted in tourist brochures.

Check out Dalton’s website at keithdaltonauthor.com.