In the heart of London, U.K., the Royal Academy of Arts became the stage for a powerful cultural reckoning.

Thirteen bronze figures stood in formation — commanding attention, reframing history and demanding a new lens through which to view the past.

The First Supper, a monumental sculptural installation by Bahamian-born, New York, N.Y., U.S.A.-based artist Tavares Strachan, was unveiled as part of the Royal Academy’s groundbreaking exhibition, Entangled Pasts, 1768 – Now: Art, Colonialism and Change.

With The First Supper, Strachan reimagines one of Western art’s most iconic religious images — Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper — through a contemporary and radically inclusive lens. In place of da Vinci’s European apostles, Strachan assembles a pantheon of Black excellence: Shirley Chisholm, Marsha P. Johnson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Haile Selassie I, and other luminaries whose contributions have shaped history yet remain underacknowledged in traditional narratives.

Memory and Erasure

This reconfiguration asks a fundamental question: Who gets remembered, and who gets erased?

Strachan’s work isn’t just revisionist — it’s restorative. It confronts centuries of exclusion in art history and challenges the Eurocentric canon that has long defined genius, divinity and cultural worth.

In doing so, The First Supper serves as both a counter-monument and a site of radical imagination. It doesn’t simply critique what came before; it builds a new visual vocabulary — one where Black figures are not anomalies or afterthoughts, but central and celebrated.

Caribbean Roots

The artist draws heavily from his Caribbean upbringing and diasporic memory. For many in Black communities, The Last Supper hung in dining rooms and churches, a sacred symbol often replicated despite its lack of cultural representation. Strachan disrupts this inherited iconography, replacing reverence for the original with a bold assertion of new meaning. The table, in his hands, becomes a site of confrontation, celebration and healing.

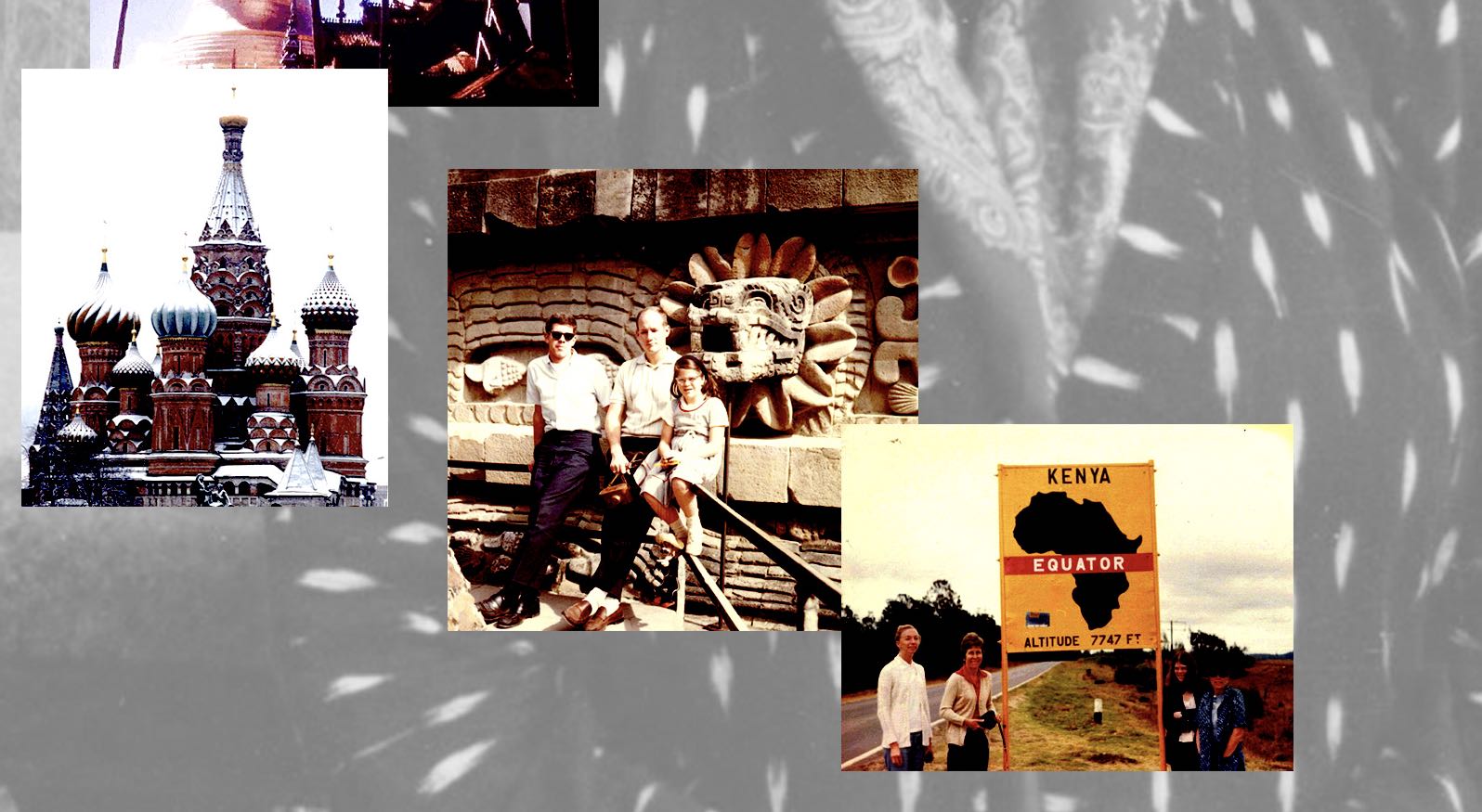

Born in Nassau, raised in Bahamian culture, educated in the U.S. and now living in New York, Strachan’s global presence adds complexity to his work. His art has been exhibited from Venice to London, Los Angeles to Lagos — mirroring his own movement across borders and cultural contexts.

The First Supper serves as both a counter-monument and a site of radical imagination.

This transnational existence is central to how Strachan creates: straddling geographies, histories and identities with a fluency that allows him to connect local memory with global impact.

Betrayal and Transformation

Strachan’s decision to insert himself as Judas — the biblical figure synonymous with betrayal — is one of the work’s most provocative choices. In doing so, Strachan implicates himself and invites viewers to reflect on their own roles within systems of power and oppression. It’s a gesture that speaks to the complexity of identity, especially for those of us who navigate multiple cultural inheritances.

Judas, in this context, is not just the betrayer, but also a symbol of complicity, transformation and the ongoing negotiation of self in a fractured world.

This layered identity resonates deeply with the lived experiences of Third Culture Kids (TCKs), Adult Cross-Cultural Kids (ACCKs) and anyone navigating the nuances of hybrid cultural belonging. As someone who has lived, worked, and traveled between the U.S., Europe, and the Caribbean, this writer sees in Strachan’s work a mirror of her own cultural multiplicity.

Strachan’s sculptures speak not only to Blackness as a monolith but to the richness and diversity within it — to the intersections of gender, geography, politics and spirituality that shape the diaspora.

Reparation

The First Supper doesn’t just offer representation — it offers reparation. It calls into question who has historically been allowed to take a seat at the table and who continues to be left out.

In claiming space for these icons of Black excellence, Strachan reminds us that inclusion isn’t about assimilation; it’s about transformation. He doesn’t ask for permission to enter the canon — he remakes it entirely.

Judas, in this context, is not just the betrayer, but also a symbol of complicity, transformation and the ongoing negotiation of self in a fractured world.

What is most striking about this work is its unapologetic grandeur. Cast in bronze and elevated on plinths, the figures exude reverence, power and grace. They are not merely subjects of history — they are history-makers. Strachan’s visual language is assertive yet poetic, rooted in ancestral wisdom and futuristic vision. Through his art, he invites us not only to remember, but to reimagine.

In an age where institutions are being called to reckon with their colonial pasts and reimagine more inclusive futures, The First Supper arrives as both a challenge and a gift: It challenges us to see who we’ve overlooked — and why. But more importantly, it gifts us with a new framework: one that honors complexity, uplifts the marginalized, and reclaims the table not just for representation but for liberation.

Tavares Strachan’s The First Supper is more than a sculpture. It is a cultural intervention. A reckoning. A reclamation. And most importantly, it is a declaration: that Black excellence belongs not on the margins, but at the center of our collective story.